During their time at Black Mountain College, Robert Creeley and Dan Rice collaborated on one of the most significant, if undervalued, works of postmodern poetry and art. All That Is Lovely in Men, published by Jonathan Williams as Jargon 10, marks the first appearance in book form of many of Creeley’s best known works, including his oft-cited and most commonly anthologized poem, “I Know a Man.” Similarly, Rice’s minimalist, suggestive drawings, exemplify some of his best work from the period, work that impressed the likes of Franz Kline and Robert Rauschenberg, among others, and would continue to be a hallmark of his practice as an illustrator through the 1970s. Printed in a run of only 200 copies, however, the book has remained out reach for most scholars, and so has not enjoyed the recognition it deserves. In addition to the tiny circulation and rare status of the work, Rice’s limited reputation, compared to Creeley’s, may also account for the omission. As Creeley recalled in a 1976 interview, he and Rice “moved in very different ways” soon after the College’s closure: “Dan really went the trip of the ‘starving artist’… I remember the time when he was passing out in the street, surviving thanks to the affection of people like Rauschenberg.”[1] In the early 1960s, Rice would retire from this scene to a studio in Connecticut, where, compared to Creeley’s ever-increasing fame, he would work quietly for the next forty years, far from the attention of scholars and critical acclaim.[2]

Creeley’s work, of course, has benefitted from the persistent and ever-increasing interest of scholars and critics. In fact, many of the poems published in All That Is Lovely in Men are among the most celebrated of his career. Within the large and growing field of Creeley scholarship, special attention has been given to his relationships with visual artists. Joshua Watsky, for one, has argued that Creeley’s contact with René Laubiès, rather than his early exposure to Jackson Pollock, proved the decisive connection in launching his career as a collaborator with other artists:

This first collaborative process with René Laubiès,… rather than any epiphany brought on by his initial contact with Pollock’s work, would be the incubator from which Creeley would emerge, becoming… a formidable author and partner in so many collaborations.[3]

Watsky’s reexamination of Creeley’s tutelage under Laubiès in this piece helpfully sets up further consideration of his “many collaborations” with subsequent artists like Rice. In terms of the relationship between poetry and art in these collaborations, Kevin Power, in his introduction to the interview cited above, has argued that poetics and aesthetics parallel each other in these encounters: “Action Painting and Projective Verse are parallel languages, major pushes in the definition of what it means to be ‘American,’ a locating of that particular idiom.”[4] The connection that Power draws here between “Projective Verse” and “Action Painting” is well-founded. Indeed, Creeley himself suggests that there are clear connections between the poetic principles he developed through correspondence with fellow poet Charles Olson, published subsequently in the latter’s groundbreaking essay “Projective Verse,” and the conceptual basis for then avant-garde visual art, or what he termed “Action painting.”[5] Pursuing these connections further, Barbara Montefalcone attempts to define this parallel through an investigation into the concept of “rhythm” in Creeley’s later collaborations:

Le concept de ‘rythme’ se révèle en effet de grande utilité pour l’étude des rapports entre les différents systèmes sémiotiques… C’est en effet par le rythme que le visible passe dans le lisible dans les collaborations de Creeley.[6]

Such rhythm, in fact, is at the heart of Creeley’s larger conception of “measure” and appreciation of jazz in the period. Though Montefaclone focuses on rhythm as it is exhibited in “Inside My Head,” one of Creeley’s many later collaborations with Francisco Clemente, she too notes in passing the suggestive example of “les improvisations de Charlie Parker” as another instance of the “rythme” linking Creeley’s writing with visual art in his many collaborations.[7] Though I will have more to say on her use of “rhythm” below, for now, I want to note its usefulness in exploring not only Creeley’s later work, but in understanding earlier, more explicitly jazz-inspired collaborations like All That Is Lovely in Men as well. That said, neither Montefalcone nor any of the other scholars cited above, despite their larger contributions to our understanding of Creeley’s varied relationships with visual artists, have examined his collaboration with Rice directly or in significant detail.

Recently, this omission has been recognized in important attempts to revaluate the career of Dan Rice. The 2014 exhibition and companion essay, Dan Rice at Black Mountain College: Painter among the Poets, curated and written by Brian E. Butler, has done much to remedy this, bringing Rice’s work, and his jazz-inspired collaboration with Creeley, into the larger scholarly conversation concerning the legacy and influence of Black Mountain. Building on this, I will be attempting here to bring Butler’s work into dialogue with the scholarship cited above, focusing squarely on Creeley’s understanding of rhythmic timing in relation to the projective aspects of “Action painting,” both in his attempts to conceptualize such aesthetics, but also in the instance of individual poems and the accompanying drawings by Rice printed in All That Is Lovely in Men. Ultimately, I want to show that these elements inform the “complementary sense” of measure Creeley heard in musicians like Charlie Parker, and that he saw in the drawings of his friend Dan Rice.[8] Meanwhile, for Rice, such complementarity lay at the heart of his approach to artistic collaboration. Rather than illustrate, his drawings offer a studied responsiveness, much like the practice of trading twelves in a jazz combo, where musicians would take turns alternating twelve-bar improvisations. As a jazz trumpeter who tried to teach Creeley to play music, it should not be surprising to find the logic of jazz governing Rice’s approach to collaboration. Rice, after all, had been a well-regarded jazz trumpeter, playing with Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Artie Shaw, Woody Herman, and Stan Kenton in California before entering Black Mountain College with the initial intention of studying music in 1946.[9] After leaving for a year, Rice returned to Black Mountain in 1948 to study painting, approaching it in a manner similar to his jazz trumpeting.[10] For Creeley, such an approach certainly complemented well his budding jazz-poetic. Indeed, when he arrived in March of 1954 the two quickly became friends, rooming together and even falling in love with the same woman.[11] All That Is Lovely in Men marks the highpoint of their artistic collaboration, with Rice’s drawings providing a visual response to Creeley’s poetry, both attuned to the rhythms of jazz.

1. Projecting Action Painting

Creeley’s writing on visual artists reveals the deep and abiding connection he saw between what Power has termed “Action Painting and Projective Verse.”[12] In doing so, it also provides the context within which he understood Rice’s work. As Watsky has shown, that experience began for Creeley in his encounter with René Laubiès and influenced his subsequent interactions with artists.[13] These interactions were essential for Creeley, on par, in fact, with his encounters with other writers, in connecting him to a budding postmodernism in art and literature, as well as grounding him in the kind of like-minded company he needed to develop his talents. A closer look at Creeley’s own writing on the subject will help to substantiate this.

In “Notes on Artists & Poets, 1950-1965,” Creeley reflects back on his foundational experiences with visual artists. To open the piece, he offers a bleak sketch of midcentury America, framing himself as isolated and out-of-touch: “As a young man trying to get a purchase on what most concerned me—the issue of my own life and its statement in writing—I knew little if anything of what might be happening.“[14] Against this backdrop, his discovery of a host of fellow travelers at Black Mountain College offered, by his own account, “that company I had almost despaired of ever having.”[15] Thus, through his correspondence with Charles Olson and friendships with visual artists in France and at Black Mountain, Creeley not only found out what was “happening,” but found himself as a serious poet and writer. Though, as he admits, the essay is not intended as mere autobiography, “[s]o put, my emphasis here seems almost selfishly preoccupied with me,” it’s candor offers insight into his larger need for collaboration in the creative process, whether intellectually, with fellow writers like Olson, or materially, with artists like Laubiès or publishers like Jonathan Williams.[16] In looking ahead to his work with Rice, it is important, therefore, to recall that Creeley’s collaborations are all, in some sense, based in the need for such a “company,” a need which registers not only in his relationships with artists, but in his recurrent exploration of romantic and interpersonal concerns—subjects of traditional lyric, however postmodern his approach to troubadour themes may be—throughout his career.

Once situated among such artists and writers, parallels in their approaches become clear. As Creeley recalls, the shared background led naturally to shared principles:

a number of American painters had made the shift I was myself so anxious to accomplish… they had, in fact, already begun to move away from the insistently pictorial, whether figurative or non-figurative, to a manifest directly of the energy inherent in the materials, literally, and their physical manipulation in the act of painting itself. Process, in the sense that Olson had found it in Whitehead, was clearly much on their minds.[17]

The italicized emphases here convey the main ideas of the passage; rather than the “pictorial,” the new art manifests “energy” and a commitment to a philosophical sense of “Process.” In this way, the “materials” of a composition, rather than any traditional approach to subject matter, are foregrounded. Of course, elements of such a “shift” are apparent in modernist works of art and literature as well. Creeley and Olson’s shared interest in the aesthetics and poetics of Paul Klee and William Carlos Williams, among others, exemplifies this fact.[18] Theses instances, however, mark outliers whose principles, though liable to extension, were responsive to very different contexts. As Creeley describes it, his concern, and that of his companions, diverged more sharply from Western artistic and poetic traditions in their dogged attempt to activate the materials of composition:

In like sense, all assumptions of what a painting was were being intensively requalified. Hence the lovely definition of that time: a painting is a two-dimensional surface more or less covered with paint. Williams’ definition of a poem is parallel: a large or small machine made of words. In each case there is the marked attempt to be rid of the overlay of a speciously “historical” “appreciation,” a “tradition.”[19]

Here, again, the italics convey the point: the new art, like the new poetry, turns away from representational or descriptive techniques that serve to foreground content or subject matter, in any traditional sense, focusing instead on the momentary activity of the diverse materials employed. Of course, much more could be said on the essentials of postmodernism; there is hardly space in a short essay such as this to offer an exhaustive catalogue. Consequently, it is important to recall that Creeley’s piece is presented as a series of “Notes,” as his title has it, partial jottings from his own partial vantage point. As such, there is no pretense to thoroughness or completion; the essay, instead, seeks to register the salient points of overlap between midcentury avant-garde aesthetics and poetics, as experienced by one writer. This, certainly, is in keeping with Creeley’s larger intentions for his writing. As he has it in “The Innocence,” in a phrase taken by Louis Zukofsky to be a kind of ars poetica for the younger poet’s early work, “What I come to do / is partial.”[20]

The connection made between art and poetry, though, in the passage above, guides the rest of the piece. Advancing from Williams, Creeley quotes Olson in exploring further the parallel between projective writing and then contemporary art:

the insistent preoccupation among writers of the company I shared was, as Olson puts it in his key essay, “Projective Verse” (1950): “what is the process by which a poet gets in, at all points energy at least the equivalent of the energy which propelled him in the first place, yet an energy which is peculiar to verse alone and which will be, obviously, also different from the energy which the reader, because he is a third term, will take away?”[21]

The passage chosen highlights Olson’s concern for method, “the process by which… ,” as the primary concern of writers constructing word machines capable of passing energy on to the reader. Once again, the focus here is on activity, on the reader’s active engagement in the materials—vocabulary, syntax, punctuation, etc.—as they convey energy across the page. Approaching the writing process in this way, with the page viewed as an open “field,” clearly has a relation to the painter’s stance toward a blank canvas.[22] Creeley thus pivots from his deployment of Olson’s poetics to an artistic parallel, this time citing fellow Black Mountain poet Robert Duncan:

Duncan recalls that painters of his interest were already “trying to have something happen in painting” and that painting was “moving away from the inertness of its being on walls and being looked at…” Action painting was the term that fascinated him, and questions such as “to what degree was Still an Action painter?” He recognized “that you see the energy back of the brush as much as you see color, it’s as evident and that’s what you experience when you’re looking.”[23]

“Action painting,” the desire to “have something happen in painting,” drives the passage. Here again Creeley’s italics insist on movement and energy as the prime motivation, and essential parallel, shared by poets and artists at the time. Attention to brush strokes, to their revelation of the painting process, becomes an essential part, in such work, of the viewer’s experience. For poetry, such effects are the result of an intensive focus on the inner workings of language. As Creeley notes in continuing, Duncan’s “The Venice Poem” was crafted on the same principles, achieving the experience of brushstrokes by insisting, through its composition, that “it is ‘not shaped to carry something outside of itself,'” directing the reader instead to its own unique process.[24] Suffice to say, the same is true of much of Creeley’s work.

Taking these points in all of their partiality, then, they are instructive, revealing the possibilities of artistic collaboration for Creeley. Clearly, his work sits best with those who share a commitment to action and energy, and who similarly feel the need for a community of mutual concern. His notes on René Laubiès and Franz Kline, which originally appeared in the Black Mountain Review around the same time of his collaboration with Rice, further support this. With Laubiès, Creeley focuses on the painter’s method: “A picture is first a picture, the application of paint or ink or whatever to a given surface — which act shall effect a thing in itself significant, an autonomy.”[25] Again, the attention here to the materials of a composition, over and above any representational subject matter, echoes Creeley’s understanding of Action Painting cited above. So, too, does his understanding of process in this case. Communicated here through a sly metaphor, Creeley is nonetheless enthusiastic about the energy of the composition, as opposed to any representational content:

But the nonfigurative painter does not begin with the bowl of apples, however much he may see it. Or if he does begin there, his process is different from that of the man who would paint it as “real.” He eats the apple, and then paints the picture. That is the sense of it. So it is a different engagement, a different sense of intent.[26]

Creeley here makes the casual image of eating an apple a metaphor for the larger break with the Western representational tradition that he prizes in his contemporaries. The still life, of course, has a central place in that tradition, so too does the symbolic value of an “apple,” redolent, as it is, with the Biblical Fall. The turn toward “process” and away from the supposed “‘real'” is thus for Creeley a shift with larger social and personal connotations; it is a “different engagement,” “a different sense of intent,” and, therefore, a very different approach to art and its world. Such ways of seeing came to him via his friendships with visual artists, as his “Note on Franz Kline” implies: “So what is form, if it comes to that… What would Kline have said, if anything. Is this thing on the page opposite looking at you too? Why do you think that’s an eye. Does any round enclosed shape seem to you an eye.”[27] The questions turned into assertions by Creeley’s unorthodox punctuation both assert the problem and offer another approach. In other words, what he appears to have learned from Kline, and attempts to convey in the passage, is that conventions—of seeing, of reading—govern our responses. Like Wittgenstein’s duck-rabbit, the grammar or rules of the game we’re playing constrain us.[28] In drawing attention to those constraints, Kline’s art, for Creeley, offers viewers another way or habit of seeing. As his assertions – “you think that’s an eye… any round enclosed shape seems to you an eye” – make clear, such conventions often only become clear when we break from them. In this way, there is “no ‘answer’ to anything,”[29] as he notes below, only responsive action, working with or against the rules as such. That Creeley’s own poetry exhibits many of the same perspectives serves to demonstrate the importance of these personal contacts for his career, complementing, as they do, Olson’s influence on his work. Though his notes dwell on Laubiès, Kline, Callahan, and Guston during his Black Mountain years, his friendship with Rice was his most immediate instance of these principles in action. Rather than learn from Rice, as he did with other artists, he created with him, putting these principles into practice.

2. Trading Ink

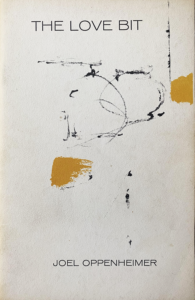

For Rice’s part, his association with Kline and others assumes a similar set of principles underpinning his work. In his collaborations with other poets, his drawings exhibit a parallel energy; rather than illustrate, they offer, in turn, a response. Though his efforts in this sphere – outside of the several drawings printed in All That Is Lovely in Men – are sparse, consisting of cover images for Black Mountain Review 6, Joel Oppenheimer’s The Love Bit, and Ross Feld’s Plum Poems, all of these efforts demonstrate modes of the “Action painting” explored by Creeley above, deployed as response, trading ink for ink, much like the jazz practice of trading twelves.

The cover image for Black Mountain Review 6 resembles, more than any other of Rice’s collaborative drawings, the work collected in All That Is Lovely in Men. Creeley, after all, was the editor of the Black Mountain Review, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, his further collaboration with Rice yielded similar results. Like the drawings for All That Is Lovely in Men, Rice’s work for the front cover and spine of Black Mountain Review 6 features an array of splayed ink dots, jagged markings, and quick pen strokes, mostly in black with occasional yellow on a white background. Meanwhile, the back cover presents what at first appears to be a similarly random display of black lines with the occasional yellow, but which, on closer inspection, present the partial outline of a face, similar to the work of Franz Kline in this period, or to Fielding Dawson’s stylized portrait of Charles Olson, which graced the cover of his memoir, The Black Mountain Book.[30] By foregrounding the strokes of ink, ranging from slowly pointed dots to deliberate lines of varying thickness and quick jagged marks, much like a writer would make in attempting to cross-out a mistake or test the ink in a pen, a kind of angular rhythm emerges, similar to the music of Thelonious Monk. As with his music, patterns build and drop almost as soon as they appear, forcing the listener, and in this case the viewer, to recalibrate in mid act. The sparse use of color adds to this effect, providing an alternate lightness to the otherwise brooding black-and-white design. Rice’s work here, as elsewhere, responds well to the writing featured within. As the table of contents for the issue shows, contributions included not only projective poetry by Creeley, Charles Olson, and Robert Duncan, but also writing by lesser known Black Mountain colleagues like Hilda Morley and student-disciples like Joel Oppenheimer, Michael Rumaker, Jonathan Williams, and Fielding Dawson. Moreover, sympathetic work by the British poet and founder of Migrant Press Gael Turnbull appears alongside the more traditional approach of Canadian poet Irving Layton, while photographs by Jess Collins appear in the same issue with drawings by Philip Guston. And yet, eclectic as the list appears, it still leaves out the contributions of three major poets: Louis Zukofsky, Lorine Niedecker, and Denise Levertov, each of whose work varies in style and interest. In creating cover art for such a collection, Rice offers his own varied form of response to the issue’s contents, actively exploring his materials in ways that reflect Creeley’s projectivist interests, evident in his earlier art criticism, by varying the rhythm and approach in his drawings, riffing, in a sense, on the issue’s collection of styles and approaches to visual art and writing.

Rice’s other two collaborations, with Joel Oppenheimer and Ross Feld, demonstrate a similar approach, opting for responsive collaboration as opposed to illustration, while also displaying shared differences with the earlier Creeley collaborations. The one biographical constant through all three book-length collaborations with poets, however, was Black Mountain College; whether working with poets, like Creeley and Oppenheimer, or publishers, like Jonathan Williams, all three books are clearly the product of the BMC community’s extended sphere of influence. In this context, it is perhaps unsurprising that Rice’s use of spare spots of ink and suggestive geometrical shapes continues in these drawings. There is once again a kind of rhythm to their spatial appearance, this time augmented by the lyrical harmony of a pair of circles in black ink, accompanied by strokes of vibrant yellow and, in the Feld collection, royal blue. These commonalities aside, each drawing responds to its companion poems somewhat differently, and their differing actions deserve further attention.

Figure 1. Dan Rice, Cover. (In The Love Bit. By Joel Oppenheimer. Totem Press/Corinth Books, 1962.)

In The Love Bit, Rice’s cover drawing appears designed especially as a response to the collection’s title poem and, as such, the book’s overarching concerns (Fig. 1).[31] There, the interlocked circles are created through layered pen strokes whose movement seems both to press together and to stretch apart: the vertical line on the upper-right-hand side of the page, next to the smaller, more tightly drawn circle, shortening the space, forcing the two circles to appear close, while the horizontal line above the more loosely drawn circle pulls in the opposite direction, suggesting some movement apart. The color incorporated into the cover adds to this tension, at once brightening the otherwise black-and-white image, while insisting on the earthiness of the artist’s materials; its yellow, in fact, is closer to ochre and so is almost clay-like, its earthy insistence reinforced by its crude application via a palette knife, whose rectangular outline is clear in the streaked paint. In this way the mundane both colors and constrains the pair in Rice’s cover image, its suggestiveness a fitting response to the couple explored in Oppenheimer’s title poem, where a rainbow of color lights their “ill- / omened days,” before giving way to the “black” and “brown” of night.[32] In color as in movement, the couple are brought together and pulled apart; as the closing lines have it, “we make it crazy or / no,” their love, by turns, unifying and alienating,[33] much like the pair in Rice’s image.

Figure 2. Dan Rice, Cover. (In Plum Poems. By Ross Feld. The Jargon Society, 1972.)

In 1972 Rice would team up with Jonathan Williams once again and contribute the cover design and a drawing for Ross Feld’s Plum Poems, published as Jargon 71 (Fig. 2).[34] The word “plum,” in fact, appears in most of the poems printed in the collection, jostling for attention with allusions to Greek myth, Bunny Berigan, the Beatles, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, among others. The range of reference is in keeping with the playfulness of the book’s title: plum, whether understood as a kind of fruit, an object of desire, or, in slang usage, a pair of testicles, offers an abundance of wordplay for the writer to explore. While Feld happily takes up this task in his poetry, Rice, too, does so in his drawings.

As with his design for Oppenheimer’s book, Rice’s work for Feld draws on geometrical shapes and color. Indeed, though there is a similar sense of responsiveness to the poetry, these images bear little resemblance to his work with Creeley. On the covers, color dominates. The front, once again, consists of a white background, this time with no title or author name, where two plum- – or testicle – shaped circles are separated by a thick vertical line, all in black, while alternating horizontal and vertical strokes of bright blue and yellow border the image. While the bright colors encourage a sense of whimsicality, the geometrical shapes’ resemblance to both plums on a stem and a kind of crude, bathroom drawing of male genitalia parallels the playfulness within. In fact, the inside drawing, opposite the title-page, insists even more so on the plums as also slang metaphor for testicles, blurring the line between the two by forcing the viewer to consider both. The combination of the academic and the crude appears similarly in the poetry, making for a series of variations on the theme of “plums.” In all of these ways, however, Rice’s drawings for Feld’s collection refrain from any attempt to illustrate, offering instead a responsive playfulness, just as his earlier work for Oppenheimer and Creeley. Indeed, Creeley’s rhetorical question from his essay on Kline, “[w]hy do you think that’s an eye,” could apply equally to the ways in which Rice here plays with visual conventions in his rendering of plums.[35]

3. A “Complementary Sense”

Creeley’s introductory note for All That Is Lovely in Men frames the work that follows. In it, he argues for a “complementary sense” between the improvised jazz of “Charlie Parker… and Miles Davis” and that of the poetic lines in the pieces gathered for the collection.[36] This parallel or responsive “rythme,” as Montefalcone has described it,[37] extends to the interaction between Creeley’s poetry and Rice’s drawings as well. There, the complementarity is evident in Rice’s handling of materials, color, and line. The bebop, or jazz, source for such choices may be less evident at first, but have been subsequently emphasized by Creeley, as a closer look at the poetry of All That Is Lovely in Men should demonstrate.

Among the poems selected by Creeley for the collection, “The Whip” best shows the jazz parallel he draws in the preface. Having appeared a year earlier, in The Black Mountain Review‘s fall 1954 issue, and reprinted here without revision, “The Whip” may seem like an unlikely candidate. A poem that appears to explore guilt, infidelity, and the power relations within a couple at the time of Creeley’s separation from his first wife Ann, and competition with Dan Rice for Cynthia Homire’s affection, it may appear to be an odd fit in an examination of his jazz-inspired poetic.[38] Robert Duncan, for instance, read the poem as an extension of troubadour tradition, a modern update where the other woman is the Dark Lady of Dante and Cavalcanti.[39] An essential part of that update, however, is Creeley’s approach to rhythm. Indeed, he seemed to feel that by getting the timing right authentic content and, ultimately, form would follow. As he explains in his Paris Review interview with Linda Wagner, “I felt that the way a thing was said would intimately declare what was being said, and so therefore, form was never more than an extension of what it was saying… It’s the attempt to find the intimate form of what’s being stated as it is being stated.”[40] When read in the context of his analogy with jazz in the short, prefatory remarks, it would seem that any and all of Creeley’s poetry from the collection could be shown to exhibit his jazz-inflected approach to rhythm. While not untrue, Creeley took special care in insisting upon the jazz inspiration at work in “The Whip.”

In fact, as opposed to other works from the period, Creeley himself later glossed the poem’s jazz influences explicitly. In “Form,” a short piece published in 1987, he elaborates on the poem’s relation to Charlie Parker:

“The Whip” was written in the middle fifties… [and] it is music, specifically jazz, that informs the poem’s manner in large part. Not that it’s jazzy, or about jazz—rather, it’s trying to use a rhythmic base much as jazz of this time would—or what was especially characteristic of Charlie Parker’s playing, or Miles Davis’, Thelonious Monk’s, or Milt Jackson’s. That is, the beat is used to delay, detail, prompt, define the content of the statement or, more aptly, the emotional field of the statement. It’s trying to do this while moving in time to a set periodicity—durational units, call them. It will say as much as it can, or as little, in the “time” given. So each line is figured as taking the same time, like they say, and each line ending works as a distinct pause. I used to listen to Parker’s endless variations on “I Got Rhythm” and all the various times in which he’d play it, all the tempi, up, down, you name it. What fascinated me was that he’d write silences as actively as sounds, which of course they were. Just so in poetry.[41]

Creeley’s description of Parker’s influence can be better understood in the light of his halting reading of the poem. Recordings, such as the one collected as part of “Rock Drill #3,” which exhibits well his habit of pausing at the line ends, famously, in imitation of his mistaken assumption about William Carlos Williams’ reading performance, make this clear.[42] Although the poem is not concerned in any obvious way with jazz, its execution bears a clear resemblance to jazz in its enfranchising of silence. In moving from one line to the next, the speaker appears to search for and dramatically find words to continue, to give voice to his emotional confusion. In a similar way, Parker or, more pointedly, Miles Davis in his Birth of the Cool recordings, then newly compiled and released, would employ silence while searching through an improvisation.[43]

Moreover, like Parker and Davis, who frequently worked both with and against a driving rhythmic pulse, Creeley’s speaker works with and against what he terms a “set periodicity.”[44] While this can be understood as the couplets that predominate the poem, it is even more apparent in the syntactical thrust of the language and the tetrameter rhythm the opening line introduces. Creeley returns to this rhythm regularly – regularly enough, that is, to cause the shorter lines to fill the seemingly missing space with a pointed silence, as the speaker searches for the next line to continue. The line breaks create a pattern of more and less dramatic changes. Just as Parker’s improvisations can move in small steps one moment, then, say, leap over flatted fifths the next, so, too, with Creeley’s line breaks. As a result, syntactical breaks become more meaningful, with the resulting pauses necessitated by his intention that “each line is figured as taking the same time” creating pregnant pauses, Parkeresque uses of “silences as sounds.”[45] At this point, it may also be helpful to recall that Parker’s music is instrumental – i.e., it’s content is its method. Creeley’s notes on “The Whip” as a jazz poem seem to take a similar approach toward words; it’s as though they are notes or chords whose meaning comes from the various combinations in which they can be manipulated. Hence, also, the importance of line-breaks and rhythmic variety in creating meaning by complicating the syntactical relations of common prose and speech, revealing the layers of possibility implicit in their typically one-dimensional usage, bringing them, in other words, into a fuller, three-dimensional reality.

“The Whip” can be shown to exhibit these methodological aims in a number of ways. The breaks at lines two, three, four, eleven, and seventeen, for instance, separate modifiers from the nouns and phrases they modify: “my love… a flat / sleeping thing,” “She was / very white / and quiet,” “I was / lonely,” and “I think to say this / wrongly.”[46] The resultant pauses suspend identity, forcing the reader to understand these characters as fractured and out of tune, both syntactically, in terms of the line, and emotionally, as befits the drama of the poem. More dramatic suspensions of sense come with more severe syntactical breaks, such as in lines 6, 9, and 10, where subjects are separated from their predicates: “I / also loved,” “she / returned,” “That / encompasses it.”[47] The effect here is more extreme, causing the reader to recalibrate the syntax of multiple lines in the course of piecing together a meaning that wanders, much like the man’s affections, and can only partially, on occasion, be contained in end-stopped lines. In all of these ways the syntactical complexity created by the varying line lengths works to develop the sound and sense of the poem in a way parallel to the meandering solos of an improvised jazz performance.

Such deftness in the handling of line-breaks affects the poem’s rhythm as well. In examining rhythmic patterns in his work, it should be noted that although projective verse seeks to make a decided break from the rhythms of closed verse, Creeley and Olson continued using traditional terminology for feet and meter in discussing their work.[48] For Creeley in particular this makes sense, given his approach to free verse in short forms. As Marjorie Perloff has shown in scanning Creeley’s work from this period, “[t]o call such poetry ‘free verse’ is not quite accurate,” because whether it is the number of words per line, or the shifting rhythmic patterns of jazz, “something is certainly being counted.”[49] In the opening stanza, the poem’s rhythm is mimetic. For instance, in line one, the iambic rhythm of “I spent a night” is inverted, fittingly, with “turning,” which substitutes a trochee for an iamb.[50] Line two, similarly, could be said to intersperse a pyrrhic and a trochee, in the middle four syllables of the line, varying from the iambs and trochees that open and close, to give the effect of a “feather’s” lightness.[51] However, these traditional lines provide merely the base beat or rhythm section for Creeley’s subsequent variations. In doing so, the approach to rhythm here resembles closely Creeley’s understanding of jazz’s influence on the “hearing or thinking” of poets associated with Black Mountain, where he notes in a later lecture that they shared an appreciation for bebop’s ability to rework standard melodies:

This music is coming, almost without exception, from… what they call old standards, songs that are immensely familiar. The chordal base and/or the melodic line is cliché—usefully cliché… the chords are kept as the ground; [but] the rhythm, the time can shift, and will shift dramatically.[52]

The perception here of using an “old standard” as the basis for new variations presents well Creeley’s approach to poetic rhythm in All That Is Lovely in Men. Indeed, as he goes on to explain in the same lecture, bebop or jazz sparked “what the imagination was then of prosody… what a particular cluster of poets where then trying to work with.[53]” In keeping with this, the following lines contract and expand, employing the silences heard in absence of the remembered beats introduced in lines one and two to convey the shifting of a ponderous weight, as the speaker works out of the conventional opening and through the “whip” of conscience.[54] As with the use of syntax above, the rhythmic breaks here probe the subject, rather than merely imitate it, as the opening lines appear to do. Time and again an iambic rhythm reappears, only to be broken, shifted, and complicated, much as Charlie Parker in the midst of a solo might return to an early melody as a pivot or bridge to a further exploration of an unexplored note in the scale, or a shift to a relative or other alternative key altogether. Line six, for instance, appears in a rough iambic pentameter, “the roof, there was another woman I,” only to pivot, in the next line, into a passage that doesn’t accord with traditional meter at all, “also loved, had.”[55] A four-syllable line with three stresses, its rhythm is largely trochaic and so reverses the direction of the previous line. This way of changing course, of darting back and forth, while turning the subject over and over again, is characteristic of the poem. Rather than mimic the sense of the words, it plays them as sounds whose weight advances the larger conflict introduced by the opening, just as Parker fathoms the full possibilities of a melody by playing it in as many different directions as possible. Creeley continues to improvise over top of the iambic beat of the poem throughout, ending abruptly with the trochaic “wrongly.”[56] Like a snare hit or trumpet flare, the poem’s rhythm doesn’t fade out, it halts. In this way, the ending bears something of the mimetic quality of the opening, whipping the speaker with a line that possesses a fittingly feminine ending. The woman’s gesture at the turn of the poem, patting the man’s back as he awakes from his dream about another lover, exhibits a mix of sincere, even gentle concern, coupled with a bracing assertion of power. Indeed, given Creeley’s own marital problems at the time, it is difficult not to read the poem biographically.

Figure 3. Dan Rice, “The Whip.” (In All That Is Lovely in Men. By Robert Creeley. The Jargon Society, 1955.)

The accompanying drawing by Rice trades on similar themes (Fig. 3).[57] Viewed in conjunction with Creeley’s title, the ink appears to lacerate the opposing page, whipping vertical strokes from top to bottom. The fainter portions of these lines appear like scratches on flesh and alternate with areas where Rice has allowed the ink to gather into think dots and bulbs, like blood weeping from a series of wounds. In fact, viewed in this regard, the page resembles a back that’s been whipped, where dots and tracks of ink mark its wounds. In this way, the image responds by drawing out and brooding upon the metaphoricity of the poem’s title. Although Creeley calls the piece “The Whip,” the closest the poem comes to this, literally, is the woman’s hand patting the speaker’s back. Like a jazz soloist exploring the notes of a chord progression, Rice calls attention to this element of the poem in crafting his response.

His use of materials, too, exhibits a jazz-like exploration of rhythm. As the eye moves from mark to mark, it is led through an array of vertical and diagonal lines of varying thickness, alternated with dots of varying size, and all punctuated, of course, by large stretches of blank space. Like a Miles Davis trumpet solo, these markings enfranchise the silence of the blank page, incorporating it into the rhythm involved in moving from line to dot and so on. In fact, Creeley had praised Charlie Parker for exhibiting just this skill in the essay cited above, where he extols the saxophonist for writing “silences as actively as sounds.”[58] Rice’s drawing applies a visual parallel, sounding silences in much the same way as Creeley’s jagged line-breaks, highlighting the length and brevity of their duration through their juxtaposition with opposing forms. These alternations appear both on a full-scale glance at the image, but also upon closer inspection. Just as the dots vary in shape and size, so too the vertical and diagonal lines. Some are composed of a mix of vertical strokes and tiny dots, others consist of numerous tiny dots either tightly packed together, like a swarm of insects, or stretched apart, like the dotted lines of a child’s coloring book. The variation, again, adds to the image’s rhythmic variety, moving the viewer’s eyes through a series of slides and stops, of quickly pointed dots and blots that straddle large expanses of white space. In this way, Rice’s tempi, punctuated by the determined use of silence, makes a fine visual analogue with Creeley’s poetic rhythms.

Of course, as an abstract image, these rhythmic shifts also employ conventions of line and shape to suggest readings other than, or in conjunction with, the whipping movement explored above, in a kind of visual layering that parallels the poem’s use of figurative language in its inducement to the viewer to look again. Anatomical images can be glimpsed throughout: something like a nightmarish, ghostly face crying out on the left-hand side, and the hint of male genitalia on the right, for instance. The overall effect of these is almost surreal, again, playing upon the dreamscape engaged with in the poem. As with his drawings throughout All That Is Lovely in Men, Rice’s work here depends on suggestion to convey a weight equal to that of Creeley’s poetry. Through it, he manages a depth of response that at once heightens the surface detail of the poem – the ghoulish face as image of the speaker’s nightmare – while also expanding upon less readily apparent aspects of it. The ghoul’s eyes, looked at again, appear as a pair of eighth notes on a musical staff, their beam broken, but still partially visible. Speaking at once to the broken romantic pairings explored by the poem and to the use of jazz-inspired rhythmical concepts in bearing out the exploration, the suggestion, as with other elements of the drawing, makes for a fitting and truly “complementary” response.

With their spare black marks against a large white page, Rice’s drawings respond well to the bleakness of Creeley’s poetry. While Creeley’s marital troubles may account for the overall mood in part, life at Black Mountain College in the middle-fifties certainly provided its own bleakness. As Michael Rumaker’s remembrances of “pan coffee” and freezer break-ins and Fielding Dawson’s recounting of “The Pork Chop Incident” detail, the material comforts of food and drink were scarce at Black Mountain during this time.[59] Coming fresh from his own grindingly poor experiences in New Hampshire, Southern France, and Majorca, Creeley knew well that comfort would have to be sought elsewhere.[60] In many ways, elsewhere manifested itself in the form of the friendships he made at the College, ones he would later describe as the “company I had almost despaired of ever having.”[61] Such company appears in All That Is Lovely in Men through Rice’s drawings. While he did not have direct experience of marital trouble as Creeley had, the two shared a rivalry for the affection of Cynthia Homire,[62] as well as – and more importantly here – the logic of jazz improvisation, especially as traded back-and-forth in small combos, such as those featuring great pairings like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, or, later, Miles Davis and John Coltrane. Rice’s drawings intend to respond to Creeley’s poems in much the same way.

In fact, the insights gathered from listening to jazz informed not only their collaboration for the book, but the pervasive attitude for many at Black Mountain College in the 1950s. Take for instance a 1953 letter to Charles Olson, where Creeley reaffirms the predominant influence of Charlie Parker on their developing poetics:

I am more influenced by Charley [sic.] Parker, in my acts, than by any other man, living or dead. IF you will listen to five records, say, you will see how the whole biz ties in… I am not joking… Bird makes Ez look like a school-boy, in point of rhythms… This, is the point.[63]

More than “Ez” (Ezra Pound) or any other contemporary writer or artist, then, Creeley and Olson looked to jazz for a way forward. In this search, Creeley found an equally enthusiastic companion in Rice. As he reflected in a letter to Robert Duncan two years later, after the infamous car crash involving Tom Field, Black Mountain College, and especially “the pleasure of Olson, Dan Rice, et al.,” had offered him the most engaging friendships he “might hope for.”[64] That scholars have largely overlooked this aspect of Black Mountain poetics impoverishes our understanding of both the school’s history and the writers’ achievements, for, hearing jazz rhythms in the texture of the literature and art produced there at that time opens up a popular dimension of campus life that is in harmony with its larger pedagogical, aesthetic, and political ambitions. As Creeley insists, we should listen.

[1] Robert Creeley, Interviewed by Linda Wagner, in Tales Out of School: Selected Interviews (Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1993), 35.

[2] See Brian E. Butler, Dan Rice at Black Mountain College: Painter Among the Poets (Asheville: Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, 2014), 61.

[3] Joshua Watsky, “Creeley, Pollock and Laubiès: The Early Years,” Black Mountain College Studies Journal 6 (2014), N.P.

[4] Kevin Power, “Robert Creeley on Art and Poetry: An Interview with Kevin Power,” in Robert Creeley’s Life and Work: A Sense of Increment, ed. John Wilson (Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1987), 347.

[5] Robert Creeley, “On the Road: Notes on Artists and Poets, 1950-65,” in The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley (Berkeley: U of California P, 1989), 372.

[6] Barbara Montefalcone, “‘An Active and Defining Presence’: The Visual and the Verbal in Robert Creeley’s Collaborations/’An Active and Defining Presence’: Le Visible et le lisible dans l’oeuvre collaborative de Robert Creeley,” Revue LISA/LISA e-journal 5, no. 2 (2007): N.P.

[7] Montefalcone, N.P.

[8] Robert Creeley, Preface, in All That Is Lovely in Men, (Asheville: The Jargon Society/Biltmore Press, 1955), N.P.

[9] Butler, 12.

[10] Butler, 12.

[11] Martin Duberman, Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community (Evanston, IL: Northwestern UP, 1972), 417-18.

[12] Power, 347.

[13] Watsky, N.P.

[14] Creely, “On the Road,” 368.

[15] Creeley, 369.

[16] Having overseen a small press himself, the Divers Press in Majorca, Creeley’s attention to such matters certainly exceeded that of many of his peers. For a more detailed examination of his work with Williams and other small press publishers, see Kyle Schlesinger, “Getting behind the Word: Creeley’s Typography,” Jacket, no. 31 (2006): N.P.

[17] Creeley, “On the Road,” 369.

[18] For their abiding interest in Williams, see Charles Olson and Robert Creeley, Charles Olson & Robert Creeley: The Complete Correspondence, 10 vols., eds. George F. Butterick and Robert Blevins (Santa Barbara, CA and Sant Rosa, CA: Black Sparrow Press, 1980-96). For their discussions of Paul Klee, see the above cited as well, especially volumes 4, 7, and 9.

[19] Creeley, “On the Road,” 370.

[20] See Louis Zukofsky, “What I Come to Do Is Partial,” Review of The Whip, by Robert Creeley, Poetry 92, no. 2 (1958): 110-12. For the Creeley quotation, see Robert Creeley, “The Innocence,” in The Collected Poems of Robert Creeley: 1945-1975 (Berkeley: U of California P, 2006), 118.

[21] Creeley, “On the Road,” 371-72.

[22] Charles Olson, “Projective Verse,” in Collected Prose, eds. Donald Allen and Benjamin Friedlander, introd. Robert Creeley (Berkeley: U of California P, 1997), 239.

[23] Creeley, “On the Road,” 372.

[24] Creeley, “On the Road,” 372.

[25] Robert Creeley, “René Laubiès: An Introduction,” in The Collected Essays of Rober Creeley (Berkeley: U of California P, 1989), 379.

[26] Creeley, “René Laubiès,” 379.

[27] Robert Creeley, “A Note on Franz Kline,” in The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley (Berkeley: U of California P, 1989), 382.

[28] For his oft-cited duck-rabbit passage, see Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, 3rd. ed., trans. G.E.M. Anscombe (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2001), 165-8.

[29] Robert Creeley, “A Note on Franz Kline,” in The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley (Berkeley: U of California P, 1989), 382.

[30] See Fielding Dawson, The Black Mountain Book: A New Edition, Revised & Enlarged, with Illustrations by Fielding Dawson (Rocky Mount, NC: North Carolina Wesleyan College Press, 1991).

[31] Dan Rice, Cover, in The Love Bit and Other Poems, by Joel Oppenheimer (New York: Totem Press/Corinth Books, 1962), figure 1.

[32] Oppenheimer, The Love Bit, N.P.

[33] Oppenheimer, The Love Bit, N.P.

[34] See Dan Rice, Cover, in Plum Poems, by Ross Feld (New York: Jargon Society, 1972), figure 2.

[35] See note 29 above.

[36] See note 8 above.

[37] See note 6 above.

[38] For further background information, see chapters seventeen and twenty-one of Ekbert Faas and Maria Trombacco, Robert Creeley: A Biography (Hanover, NH: UP of New England, 2001), 151-62, 188-96.

[39] Robert Duncan, “After For Love,” in Robert Creeley’s Life and Work: A Sense of Increment, edited by John Wilson (Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1987), 99-100.

[40] Robert Creeley, Interviewed by Linda Wagner, in Tales Out of School: Selected Interviews (Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1993), 30.

[41] Robert Creeley, “Form,” in The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley (Berkeley: U of California P, 1989), 492-3.

[42] On Creeley’s mistaken, creative mishearing of William Carlos Williams, see his letter to the editors of Sagetrieb 9, nos. 1-2 (1990): 270-1. For the “Rock Drill #3” performance, see the Robert Creeley page at Pennsound, Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing, University of Pennsylvania, accessed 9 September 2018, http://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Creeley.php.

[43] Listen, for instance, to Miles Davis, trumpeter, “Moon Dreams,” recorded March 9, 1950, track 3 on Birth of the Cool, released in 1956 on Capitol, Vinyl LP.

[44] Robert Creeley, “Form,” in The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley (Berkeley: U of California P, 1989), 492.

[45] Creeley, “Form,” 492-3.

[46] Robert Creeley, “The Whip,” in All That Is Lovely in Men, (Asheville: The Jargon Society/Biltmore Press, 1955), N.P.

[47] Creeley, “The Whip,” N.P.

[48] See for instance the usage of traditional terms for feet and meter in the above-cited Charles Olson, “Projective Verse,” in Collected Prose, edited by Donald Allen and Benjamin Friedlander, introd. Robert Creeley (Berkeley: U of California P, 1997), 239-49.

[49] Marjorie Perloff, “After Free Verse,” in Poetry On and Off the Page: Essays for Emergent Occasions (Tuscaloosa, AL: U of Alabama P, 2004), 155.

[50] Robert Creeley, “The Whip,” in All That Is Lovely in Men, (Asheville: The Jargon Society/Biltmore Press, 1955), N.P.

[51] Creeley, “The Whip,” N.P.

[52] Robert Creeley, “Walking the Dog: On Jazz Music and Prosody in Relation to a Cluster of Beat and Black Mountain Poets,” Pennsound, Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing, University of Pennsylvania, accessed 9 September 2017, http://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Creeley.php.

[53] Creeley, “Walking the Dog.”

[54] For a useful discussion of the reader’s perception of absent beats in poetic rhythm, see Derek Attridge, The Rhythms of English Poetry (New York: Routledge, 1982).

[55] Robert Creeley, “The Whip,” in All That Is Lovely in Men, (Asheville: The Jargon Society/Biltmore Press, 1955), N.P.

[56] Creeley, “The Whip,” N.P.

[57] Dan Rice, “The Whip,” in Robert Creeley, “The Whip,” in All That Is Lovely in Men, (Asheville: The Jargon Society/Biltmore Press, 1955), N.P., figure 3.

[58] Robert Creeley, “Form,” in The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley (Berkeley: U of California P, 1989), 493.

[59] See Michael Rumaker, Black Mountain Days: A Memoir (New York: Sputen Duyvil, 2012), 96-99 and Fielding Dawson, The Black Mountain Book, A New Edition (Rocky Mount, NC: North Carolina Wesleyan College Press, 1991), 58-79.

[60] See, for instance, the account of these years in Ekbert Faas and Maria Trombacco, Robert Creeley: A Biography (Hanover, NH: UP of New England, 2001), 54-196.

[61] Robert Creeley, “On the Road: Notes on Artists and Poets, 1950-65,” in The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley (Berkeley: U of California P, 1989), 369.

[62] See note 11 above.

[63] Robert Creeley, The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley, eds. Rod Smith, Peter Baker, and Kaplan Harris (Berkeley: U of California P, 2014), 112-13.

[64] Creeley, The Selected Letters, 143.

Bibliography

Butler, Brian E. Dan Rice at Black Mountain College: Painter among the Poets. Asheville: Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, 2014.

Creeley, Robert and Dan Rice. All That Is Lovely in Men. Asheville: The Jargon Society/Biltmore Press, 1955.

Creeley, Robert. “A Note on Franz Kline.” In The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley, 381-3. Berkeley: U of California P, 1989.

—. “Form.” In The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley, 590-3. Berkley: U of California P, 1989.

—. “The Innocence.” In The Collected Poems of Robert Creeley, 1945-1975, 118. Berkeley: U of California P, 2006.

—. Interviewed by Linda Wagner. In Tales Out of School: Selected Interviews, 24-70. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1993.

—. “On the Road: Notes on Artists and Poets, 1950-65.” In The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley, 367-77. Berkeley: U of California P, 1989.

—. “René Laubiès: An Introduction.” In The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley, 379-81. Berkeley: U of California P, 1989.

—. “Robert Creeley on Art and Poetry: An Interview with Kevin Power.” In Robert Creeley’s Life and Work: A Sense of Increment, 347-69. Edited by John Wilson. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1987, 347-69.

—. The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley. Edited by Rod Smith, Peter Baker, and Kaplan Harris. Berkeley: U of California P, 2014.

—. “Walking the Dog: On Jazz Music and Prosody in Relation to a Cluster of Beat and Black Mountain Poets.” Pennsound. Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing, University of Pennsylvania. Accessed 9 September 2017. http://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Creeley.php.

—. “The Whip.” In All That Is Lovely in Men, N.P. Asheville: The Jargon Society/Biltmore Press, 1955.

Duberman, Martin. Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community. Evanston, IL: Northwestern UP, 1972.

Duncan, Robert. “After For Love.” Robert Creeley’s Life and Work: A Sense of Increment, 95-102. Edited by John Wilson. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1987.

Feld, Ross. Plum Poems. New York: The Jargon Society, 1972.

Montefalcone, Barbara. “‘An Active and Defining Presence’: The Visual and the Verbal in Robert Creeley’s Collaborations/’An Active and Defining Presence’: Le Visible et le lisible dans l’oeuvre collaborative de Robert Creeley.” Revue LISA/LISA e-journal 5, no. 2 (2007): N.P.

Olson, Charles. “Projective Verse.” In Collected Prose, 239-49. Edited by Donald Allen and

Benjamin Friedlander, introd. Robert Creeley. Berkeley: U of California P, 1997.

Oppenheimer, Joel. The Love Bit and Other Poems. New York: Totem Press/Corinth Books, 1962.

Oppenheimer, Joel. “The Love Bit.” In The Love Bit and Other Poems, N.P. New York: Totem Press/Corinth Books, 1962.

Perloff, Marjorie. “After Free Verse.” In Poetry On and Off the Page: Essays for Emergent

Occasions, 141-67. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2004.

Power, Kevin. “Robert Creeley on Art and Poetry: An Interview with Kevin Power.” In Robert Creeley’s Life and Work: A Sense of Increment, 347-69. Edited by John Wilson. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1987.

Rice, Dan. Cover. In The Love Bit and Other Poems, by Joel Oppenheimer, figure 1. New York: Totem/Corinth Books, 1962.

—. Cover. In Plum Poems, by Ross Feld, figure 2. New York: The Jargon Society, 1972.

—. “The Whip.” In All That Is Lovely in Men, by Robert Creeley, figure 3. Asheville: The Jargon Society/Biltmore Press, 1955.

Watsky, Joshua. “Creeley, Pollock and Laubiès: The Early Years.” Black Mountain College Studies Journal 6 (2014): N.P.

Joseph Pizza completed his DPhil in English Language and Literature from the University of Oxford in 2012. He is currently an Associate Professor of English at Belmont Abbey College, where he teaches courses in modern and contemporary literature. In addition to his work on Dan Rice and Robert Creeley, he has also written recently on Charles Olson, Nathaniel Mackey, and Harryette Mullen.